The Roof may have caved in but the Building still stands: The Motif of the Assembly Hall in Chinese Contemporary Art

6th October, 2020

The term ‘assembly hall’ conjures memories of sitting cross-legged on the cold floor in rows by my peers, while the principal addressed the school. I imagine many people can relate with their own version of the long monotonous speeches and numb limbs, that constituted school assemblies. For people living in China during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) the assembly hall does not evoke the same innocent, mundane experience. The Assembly Halls of the Cultural Revolution were built for the purpose of governmental control and were more often than not a negative affair for attendees. Assembly Halls were located throughout China to maximise the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) outreach. The objective was to ensure the Party’s presence and influence was felt throughout the country. These Assembly Halls endorsed mass criticism, with people from all social classes exposed to ridicule and ostracisation.

A period of forty-three years has passed since the end of Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), leaving many who experienced it still alive today. Generations are still trying to navigate their childhood experiences and understand the long lasting effect the Cultural Revolution has had on their consciousness. The Assembly Hall is not simply architecture but symbolises the struggle and humiliation that people faced at these sites during the Cultural Revolution (Zheng 2014, 10).

Contemporary Chinese artists continue to engage with the Cultural Revolution and the collective experience, as endured, by the population. Many of these artists were present at the time of the Cultural Revolution and know first-hand the reach of the Cultural Revolution’s shadow. The artists in question approach the subject with duality, to simultaneously comprehend history and examine contemporaneity. The Assembly Hall serves not only as a symbol for the Cultural Revolution, but also of the ongoing exhaustive control as exercised by the Chinese government.

Shao Yinong & Muchen, Gaotang, 2003, C-Print, C-print, 122 x 168 cm.

With the rise of technology, media has become the device to deliver messages and establish common thought amongst a population. Media allows the Chinese government to effectively infiltrate the homes and workplaces of citizens, with little effort on their part. By censoring the media available and controlling what access the Chinese people have to international sources, the CCP manipulates the population through forced ignorance. The extent of suppressed knowledge became apparent when travelling in China. While extensive political demonstrations were taking place in Hong Kong, there was no coverage of the events in mainland China. It was only those residents with access to a Virtual Private Network (VPN) that were aware of the protests taking place in their own country. The CCP are well versed in the art of knowledge manipulation and it is a powerful tool they continue to brandish. Parallels can be easily drawn between this current filtering of information through the internet by the CCP and the propaganda that was spoken at the Assembly Halls during the Cultural Revolution.

Contemporary Chinese artists use the Assembly Hall, as iconography of the Cultural Revolution and as an allegory for Contemporary China. Painter Zhang Linhai and photographer pair Muchen and Shao Yinong, are three artists who have enlisted the Assembly Hall as a motif in their oeuvre. As children themselves during the Cultural Revolution, these artists reflect on the lived experience of the Cultural Revolution and the Chinese government’s grasp since. While the subject matter between the artists correlate, their approach to the subject is dissimilar. Muchen and Shao assess the subject through a documentary practice, taking pictures of Assembly Halls around the country, as they stand in their current state. In comparison, Zhang’s approach is very personal, opting to reflect on his own childhood experiences of growing up in the Cultural Revolution.

Due to the intimacy of Zhang’s practice, it is valuable to understand his biographical details. Zhang was born in Shanghai but was adopted from a young age and moved to the Taihang Mountains in the north of China. During the Cultural Revolution Zhang’s foster parents were deemed landlords and counter-revolutionaries. They were tormented to such a degree and lived in such fear that when Zhang succumbed to illness, his parents feared to seek for assistance. The lack of treatment left Zhang with necrosis in his right hip joint and severe physical disability in his legs. The lack of social acceptance and government support in China for physical disabilities, hascaused barricades and struggles for Zhang his whole life, particularly in the avenues of employment and education (Hong 2018, p. 23). While physical disability has held tribulations for Zhang, the emotional trauma from the Cultural Revolution has been just as significant in moulding his life.

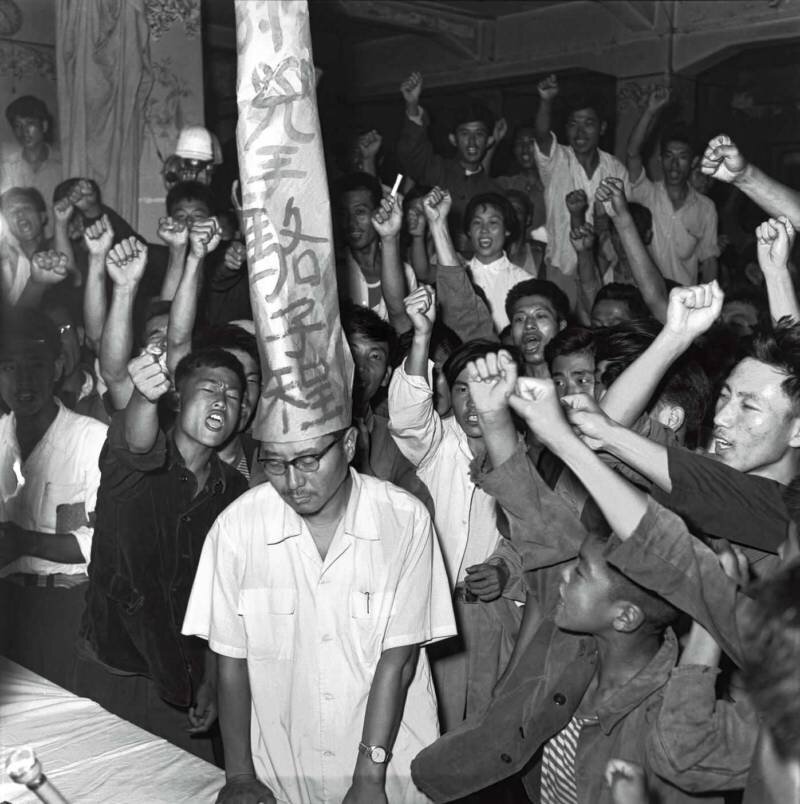

A struggle session at an assembly hall.

Zhang admits to having a lonely childhood, from which he has never been able to detach. His childhood was filled with collective activities (Zhang 2019). However, always being one of a larger group seems to have left Zhang with a sense of disconnection. After witnessing, at a young age, the vileness that can come from crowds it is understandable that solitude would become appealing to Zhang. Zhang, however, is not alone in his studio. The presence of the figures in Zhang’s paintings are palpable and entering his studio feels much the same as entering a room crowded with people. Paintings cover every wall and shelf of the large studio space. In visiting Zhang’s studio it becomes apparent that Zhang paints for himself, using painting to create a world in which he can exist. He has brought teddy bears, dolls and animals from his childhood in rural China to life once more in his paintings. The figures and characters in his paintings appear to keep Zhang company. All involved, Zhang and his subjects, find a semblance of comfort from their perpetual loneliness by co-existing in the safe space Zhang has created.

A considerable amount of Zhang’s oeuvre could be referred to as magical realism as he blends the mythical with the everyday in a comment on modern society. Zhang places common symbols and occurrences of the Cultural Revolution often into landscapes that are otherworldly or else stretches plausibility by altering proportions or having a person fly. These works are eerie for they are both innately familiar and unnatural.

The series I wish to draw attention to is Zhang’s Theater Series (2015) which focuses on the subject of the Assembly Hall. This series stands apart from much of his earlier work as the composition is comparably minimal. Theater Series is characterised by the presence of an Assembly Hall situated on the horizon of an otherwise barren rural landscape. The third element is that of a single figure or crowd of people, shown as they walk to or from the hall or at attention in front of it. The figures are clothed in black uniforms at varying stages of undress. In every instance the head of the figure is bowed and the Assembly Hall protrudes above them. The halls are all individual but their common architecture of a stage with red curtains flagged by wings on either side and a domed or triangulated roof where in the tympanum a gold star sits, denotes them as Assembly Halls. The Assembly Hall may stand in the prominent position of status in these works but the audience’s focus and appraisal is largely consumed by the people.

In Theater Series - 4 (2015) snow covers the ground as an expanse of people stand naked while being addressed at the Assembly Hall. This work can be understood as a metaphorical visualisation for how people were humiliated and emotionally stripped bare at this sort of ceremony. Theatre Series - 1 (2015) shows a young boy in the foreground with his eyes downcast and the collar of his jacket up over his ears in an attempt to protect himself from the world around him. These works are fiercely poignant as Zhang has laid bare his psychology with the honest expression of his emotional reality.

Zhang Linhai, Theatre Series, 2017, mixed media on board 90 × 120 cm

While Zhang paints as a method of processing his own past, he acknowledges his experience was a reality for many, understanding as literary critic Ban Wang remarks ‘individual experience could not be set apart from collective experience’ (106). For Zhang art serves as a link between the individual and the sense of ‘being-in-common’ (Berghuis 2014, p. 20). The imagery Zhang uses would be familiar to people of his generation. The large crowds of people with shaven heads, the speaker in a public space, the Mao constituted ‘fashion’ and the Assembly Hall were common experiences of the Cultural Revolution. Zhang brings forth these archetypes of the collective unconsciousness from the Cultural Revolution to be assessed under a contemporary consciousness.

Muchen and Shao approach the collective memory of the Assembly Hall via a more documentative approach. While Zhang creates his work by reliving his past experiences, Muchen and Shao have alternatively elected to research the variant experiences of others who lived through the Cultural Revolution. The couple began the series, Assembly Hall, after Shao went in search of his grandfather’s shop, only to find that an Assembly Hall stood in its place. For the following year the scene plagued Shao’s mind, which prompted Muchen and himself to continue the series to uncover more information on the state of the Assembly Halls and their place in contemporary China (Shao 2019).

When Muchen and Shao commit to one of their projects they dedicate a large part of their life for considerable length of time. It is evident that their practice is their life. The way in which they speak of their photographs is as if recounting personal memories. Their documentative approach is not so they distance themselves but an attempt to carry the realities of those in the past as they cannot do so for themselves. Rather than starting from their own memories they look at their immersive practice as a way for the subjects they take pictures of become part of their personal story. Each photograph makes an impression on the heart of Muchen and Shao, which they carry forward. The pair travel the expanse of China in search for new understanding on the situations of people past and present.

In their series, Assembly Hall, Muchen and Shao acknowledge that people hold different attitudes towards Assembly Halls dependent on whether they were dealing or receiving the criticism. The artists’ largely unimposing approach to their practice of documenting images, allows for people to approach the subject from varying backgrounds and perceptions. The couple do not alter the scenes from how they find them, electing instead to capture the Assembly Hall in an unaltered state of existence. Muchen and Shao refer to the photographs not as images of architecture but as portraits of each individual Assembly Hall (Shao 2019). The treatment of the Assembly Hall under the genre of portraiture is to consider the character of the subject and the emotions it transposes. Muchen and Shao have attempted to capture the varying characters of these buildings that once stood for commonality.

Within the series, ‘Assembly Hall’, each work is titled by the town in which the picture was taken, in reference to its unique identity. Unlike Zhang, Muchen and Shao show the inside of the Assembly Hall, placing people back within the walls of the Hall. The common camera angle, positioned in the centre of the room taken with a wide angle lens directed towards the stage, establishes seriality in tandem while highlighting the differences between the halls. A number of the Halls are in a terminal state. Shingle (2003), for instance is only the framework of the building that once existed, with the roof having fallen apart and the ground infested with weeds. Some, such as Hongdu (2002), have been repurposed as theatres, while others have found alternate purposes as barns, factories or restaurants. All the Halls hold signifiers of their previous use. Even those buildings in the most desolate state have faded red writing on the wall or deteriorated propaganda posters visible. These references to the Halls past lives, accentuate the lingering presence of the Cultural Revolution.

The Assembly Hall was a place of hegemony and despite them no longer being used for their original function or left to decay, the mission of widespread control by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has not ceased. Art critic, Li Xianting, draws this parallel between the Assembly Hall, referencing Muchen and Shao’s series, and how it has been replaced by the internet (Xianting 2019). The form of delivery may have transitioned from spoken word and posters to internet and media but the outcome is similar. Artists use the Assembly Hall as a symbol for Chinese government control irrelevant of context. The Assembly Hall while born from the Cultural Revolution is equally representative of the circumstances in contemporary China. When speaking on their work Zhang, Muchen and Shao all stated that their work is both a reflection on the past and a comment on contemporary times. The artists have folded the fabric of time, allowing history to act as an allegory for contemporary China.

Bibliography

Berghuis, TJ 2014, ‘History and Community in contemporary Chinese art’, Journal of Chinese Contemporary Art, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 7-23 Available from Ingentaconnect. [20 July 2019].

Hong, W 2018, Theater of the Soul, The Individual, Society, ‘Time and Historical Metaphors in Zhang Linhai’s Work’, The Temperature of Dust, pp. 21-27. Linda Gallery, Beijing.

Linhai, Zhang. Interviewed by: UWA student group. (29th June 2019)

Xianting, Li. Interviewed by: UWA student group. (29th June 2019)

Yinong, Shao and Muchen. Interviewed by: UWA student group. (28th June 2019)

Zheng, G 2014, ‘Activating Memories, for the Sake of Self Salvation: A Review in the Photographic Works of Shao Yinong and Muchen’, in Shao Yinong and Muchen, pp. 6-17. Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong.